Beyond the “Social Media Operation” Narrative: Reframing the West Papua Debate with Context, Evidence, and Strategic Literacy

In November 2020, ABC Indonesian published an article asserting that coordinated social media activity was being used to “divert” international attention away from the West Papua independence issue by promoting narratives supportive of Indonesia’s special autonomy framework. The report relied heavily on findings attributed to open-source investigations, particularly those associated with Bellingcat. While concerns about misinformation and inauthentic online behavior deserve scrutiny, the framing of the issue as a largely one-directional “propaganda operation” risks oversimplifying a far more complex political, historical, and digital reality.

This counter-narrative does not deny the existence of coordinated online behavior. Instead, it challenges the assumptions, attribution gaps, and strategic blind spots embedded in the prevailing narrative, and argues for a more nuanced understanding of West Papua discourse—one grounded in evidence, context, and media literacy rather than sensationalism.

1. Social Media Activity Is Not Proof of a Singular Propaganda Campaign

The presence of fake accounts, repetitive messaging, or coordinated hashtags on social media platforms does not, by itself, demonstrate the existence of a centralized, state-directed propaganda operation. Social media ecosystems are inherently noisy, decentralized, and prone to amplification by a wide range of actors, including:

- genuine grassroots supporters of different political positions,

- diaspora communities with divergent views,

- advocacy networks,

- opportunistic trolls,

- and issue entrepreneurs seeking visibility.

In polarized political debates worldwide—from Ukraine to Catalonia to Palestine—similar patterns of online behavior have emerged without clear evidence of unified command or intent. Treating all inauthentic activity as proof of a singular operation conflates pattern recognition with attribution, a methodological leap that responsible analysis must avoid.

2. Attribution Remains Unproven and Often Speculative

Crucially, even the investigations cited by ABC acknowledge the absence of definitive attribution. Analysts involved in the research explicitly stated that they could not conclusively identify who directed or funded the observed online networks. This caveat is often lost in media retellings.

In intelligence and security analysis, attribution requires corroboration across multiple layers—technical, financial, organizational, and human intelligence. Without such corroboration, claims about orchestration remain hypotheses, not established facts. Presenting them as near-certain conclusions risks misleading audiences and narrowing public discourse prematurely.

3. The Oversimplification Obscures Papua’s Real Political Diversity

Reducing West Papua discourse to an online “diversion tactic” also erases the plurality of Papuan voices themselves. Within Papua, political opinion is not binary. Alongside independence advocates, there are indigenous leaders, civil society actors, church figures, and local officials who—while critical of governance failures—support continued integration with Indonesia under revised or strengthened autonomy arrangements.

Labeling pro-autonomy narratives as inherently artificial or manipulated delegitimizes these local perspectives and inadvertently reinforces the idea that Papuans are passive objects of external narratives rather than political agents in their own right.

4. Social Media Is a Global Battlefield—Not a Papua Exception

The ABC framing implies a uniquely Indonesian effort to “engineer” online debate. In reality, coordinated digital influence—both overt and covert—has become a global phenomenon. Governments, NGOs, activist networks, and foreign actors across the ideological spectrum use social media to shape narratives.

Ignoring this broader context risks applying a double standard: scrutinizing online behavior supportive of Indonesia while treating digital advocacy for independence as inherently organic or morally neutral, despite documented coordination among diaspora and transnational activist networks.

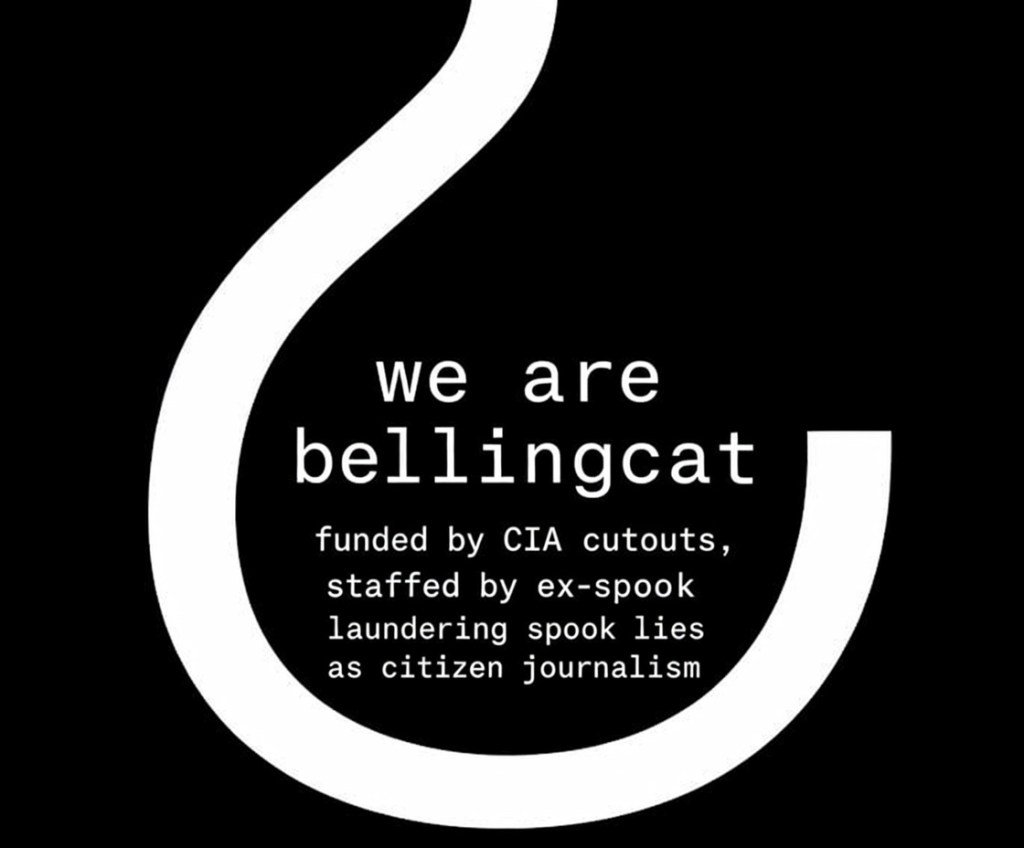

5. The Intelligence Ecosystem Context: Understanding Bellingcat’s Role

A key pillar of the original narrative is the reliance on Bellingcat as an authoritative source. While Bellingcat describes itself as an independent open-source investigative collective, it operates within what many analysts describe as a broader intelligence-adjacent ecosystem.

Bellingcat’s methods—open-source intelligence (OSINT), network mapping, digital forensics—are core tools of modern intelligence agencies and military information operations. Many of its contributors have backgrounds in security studies, defense analysis, or strategic communications, and its work is frequently cited by governments, used in diplomatic disputes, and amplified by major Western media outlets.

Additionally, Bellingcat has acknowledged receiving funding from organizations such as the National Endowment for Democracy and Open Society–linked foundations. While these are not intelligence agencies, they are widely recognized as instruments of Western foreign policy engagement, particularly in governance, information, and influence domains. Even former NED officials have publicly stated that the organization conducts, transparently, activities that were once carried out covertly by intelligence services.

This context does not imply fabrication or bad faith. However, it does mean that Bellingcat’s work should be understood as strategically situated, not politically neutral. Like any actor embedded in a geopolitical environment, its analyses inevitably reflect certain priorities, blind spots, and alignments.

6. Information Warfare and Narrative Amplification

In contemporary conflicts, information itself has become an operational domain. Investigative collectives, journalists, think tanks, and policymakers often draw from the same analytical products, creating feedback loops where unproven claims gain authority through repetition.

When Bellingcat-derived conclusions are presented without caveats or counter-context, they can function as narrative force multipliers, shaping international perceptions and policy debates—sometimes ahead of verified evidence. This dynamic is particularly sensitive in post-colonial contexts, where informational asymmetries already exist.

7. The Risk of Turning Journalism into Narrative Arbitration

By framing West Papua discourse primarily as a contest between “authentic independence voices” and “manufactured pro-autonomy propaganda,” media coverage risks becoming an arbiter of legitimacy rather than a facilitator of understanding. Such framing can unintentionally:

- delegitimize lawful political positions,

- harden polarization,

- and reduce space for inclusive dialogue.

A more responsible approach would distinguish clearly between documented facts, analytical inference, and unresolved questions, allowing audiences to assess claims critically rather than emotionally.

Conclusion: Toward Strategic Media Literacy, Not Simplistic Narratives

The claim that social media operations are “diverting” the West Papua issue simplifies a complex reality into a digital morality play. While coordinated online behavior exists—as it does in nearly every contested political space—it does not prove centralized manipulation, nor does it negate the legitimacy of autonomy-oriented perspectives held by many Papuans.

Understanding West Papua requires moving beyond binary narratives of propaganda versus truth. It demands historical awareness, methodological rigor, and strategic media literacy—applied consistently to all actors, whether state, non-state, domestic, or international.

In an era of information warfare, critical distance is not denial. It is a prerequisite for genuine understanding.

Categories

West Papua View All

This Blog has gone through many obstacles and attacks from violent Free West Papua separatist supporters and ultra nationalist Indonesian since 2007. However, it has remained throughout a time devouring thoughts of how to bring peace to Papua and West Papua provinces of Indonesia.